The following material will appear in The Kingdom of God, Volume Three: Learning War No More by Tom A. Jones to be released later this year. The book will be available from Illumination Publishers.

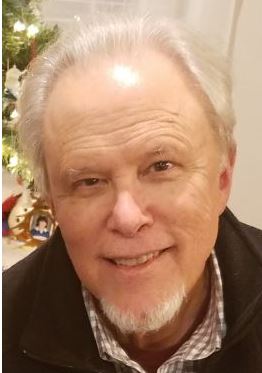

As we open this chapter and the one to follow, I want to depart from the norm and ask you, my reader, to think of me as Alabama Tom Jones. I owe that idea to a blues musician from the 1920s and 1930s named Mississippi John Hurt, but we will come to John later and how he came to influence my life. Just now, let me tell you a story with some twists and turns to help you understand the reason for my new moniker and how it relates to understanding race and racial relations through Kingdom eyes.

I was born in the town of Florence and received my college degree in the same town twenty-one years later. In between those two dates I spent almost all my pre-college years in the adjoining town of Sheffield and worked some years in a third bordering town of Tuscumbia. To round it all out, most of my Sunday mornings were spent going to church in Muscle Shoals, the fourth connected town, and the home of a famous recording studio. These “Quad-Cities” in the “Shoals Area” were all in the northwest corner of the state of Alabama.

I have complicated feelings about my home state. I have not talked much publicly or written about this, but it seems it is time that I did. It was there fifty-one years ago on the campus known today as the University of North Alabama that I first counted the cost and made the decision that Jesus would be to be the Lord of my life. It was also there that I soon began dating the one who would share these last 50 years with me. For both of these, I am most grateful. While, my wife, Sheila, would not mess with my relationship with Alabama, Jesus certainly did.

Feeling Fine in Alabama

Prior to becoming a disciple of his, I felt quite fine about being from Alabama. More than that, I felt quite proud of it, in a rebellious kind of way. In the alphabetical list of states, we were always at the top, always first to vote at the nominating conventions. And, maybe most important to me, for more than two decades of my life, we had Bear Bryant, and were often in top five in the nation in football and number 1 more often than anyone else. In 1959, the man on his way to legendary status heard the call to “come home to Mama,” and returned from Texas A&M to his alma mater, and started one of the greatest runs of championship football in American history with the Alabama Crimson Tide. Like a lot of other Alabamians (except those for Auburn), I felt he had taken me personally along for the ride.

On Saturdays I made my way to the football shrines in Tuscaloosa and Birmingham as often as possible and watched the revered coach in his houndstooth hat prowl the sidelines and lead his team. Only much later would realize I was so connected with “The Bear,” that he was almost like a second father to me. No doubt there were thousands of other Alabama boys who felt the same. Years after his death I watched a documentary on his life and found myself unexpectedly weeping – a very rare experience for me, but one revealing how deeply he had become part of me.

Besides the Bear and the Crimson Tide, I was also proud in the 1960s that we finally had a Southern politician standing up to the big shots in Washington. He was working toward a third-party run for president. He drew major media attention and would win enough electoral votes to nearly throw the election into the House of Representatives. We cheered as he appeared on “Meet the Press” and proudly stood for conservative values and “states’ rights.” He looked at Democrats and Republicans and said “There is not a dime’s worth of difference in them.” He spoke to the common man (or really the common white man). My dad said, “Son, he gets the hay down where the goats can get it.” We loved it. We loved him. His name was George C. Wallace (Yes, the same one who proclaimed “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!”)

So, my worldview was pretty simple and Alabama fit very well in it. I have a memory of being on a team bus and passing a baseball field when I was in high school. I can still see the sign on the center-field fence. It said “American Legion: For God and for Country.” That summed up life in Alabama. We prayed at Scout meetings. We had Bible reading to start school days. We prayed before Friday night football games; we sang the national anthem there and did both again at the college games on Saturdays; we went to church on Sundays; we supported our troops in Viet Nam. We were the good guys: for God and for Country. It all blended together. Never mind that we were racists and white supremacists who would, at the same time, have been greatly offended to be called that. That was me. That is where I was.

The Kingdom Breaking In

But when the Kingdom breaks in, it upsets a lot of apple carts, and, predictably, Jesus started troubling my nice little world. Not long after committing myself “totally” to him as best I understood that, I found myself on a shooting range with my R.O.T.C class, a mandatory requirement at my “gung ho” public college. I don’t know how many times I pulled the trigger of the World War II era M-1 rifle. I do remember two things about the experience. The gun had a kick much greater than expected, and I went back to my Bible and spent time thinking that I could not see Jesus doing what I had just done: practicing to shoot another human being. I had “played army” with my little buddies in the Alabama woods all through my childhood. I had dug fox holes with my guys. We had reveled in the many fictional TV shows based on World War II events. We had killed many a German and countless “Japs.” Soldiers were my heroes. But now I was re-examining my life through the eyes of Jesus and he was changing me. If I was following him, how could I possibly kill another human when I could never imagine him ever doing that?

Following Jesus was reshaping my thinking, but with more transformation needed, he soon moved into another space in December 1968 and challenged other long-held assumptions.

- It was a Friday night, as I recall, just five days before the new year. I was in an audience of 1,000 people, mostly college students from around the country, who had come to Dallas, Texas, for the four-day International Campus Evangelism Seminar.[1] It was a huge out-of-the-box experience for me.

- First time for a church event in a hotel.

- First time to ever be with a thousand people who weren’t watching sports.

- First time to spend four straight days focusing just on Jesus and his mission.

- First time to begin to grasp how the Holy Spirit fills the Christian.

- And… the first time to come face to face with my racist heart.

The speaker that night was a black minister and attorney from Atlanta, Georgia, named Andrew Hairston. I had never heard of him before that day, but I will never forget his message. His words would eventually change my worldview, my perspective and my life. He was the first man I ever heard in my family of churches apply the message of the gospel to racial attitudes, racial divisions, and racial discrimination. Of course, Martin Luther King, Jr., and others had been doing that for years, but I wasn’t listening. According to my white Alabama culture, King and his associates were just puppets of the Communist Party.

As Andrew Hairston spoke, he carefully did an exposition of scripture after scripture, showing that racial discrimination or bias has no place in the life of a disciple. But then, as they would say in the South at that time, “He stopped preaching and went to meddling.” He described America’s fascination with George Wallace and particularly talked about how many Christians supported him. He focused in on the racism that had been at heart of the Wallace message for years. My discomfort level was on the rise as I was learning much more about what it means to be convicted by the proclamation of the message. Often such conviction is accompanied by confusion and such was the case for me. My heart was beating fast and my mind was spinning.

After he finished, I remember some of my fellow Alabamians were angry. How dare he call out our governor? How wrong it was to bring up politics in a conference on evangelism. I, on the other hand, remember being deeply troubled. Later I would see it as almost a Damascus Road experience.

Not six weeks earlier I had cast my first (and what would be my last) vote for U.S. President in 1968 for, yes, Governor George C. Wallace of Alabama. Had that been a terrible mistake? Was I supporting something quite contrary to Jesus and his Kingdom? Had I heard only what I wanted to hear and ignored the racism and white supremacy that had long been a part of the governor’s message and his appeal? But maybe I didn’t ignore it. Maybe I subtly bought into it and rationalized it. But Jesus, through Andrew Hairston, was working on me and that is what I had signed up for. I did not fight it. I wanted the transformation he brings, if sometimes reluctantly and fearfully.

An Unsettling Connection

Returning to Alabama from the Dallas event, my story took an interesting turn. My involvement in our campus Christian fellowship had led to me becoming the president of the group. It was now several months after George Wallace’s presidential run and a wave of “decency rallies” were being held around the country. One of the largest was in Miami where they drew 35,000 teens to say “no” to the antics and language of rock musicians like Jim Morrison and the Doors.

The city of Florence, Alabama, in coordination with the university, decided to sponsor one of these rallies for decency with, yes… George Wallace as the keynote speaker. Somehow, ironically it seems now, my name was picked out of the leaders of various campus religious groups, and I was invited to share the dais with the governor and offer the opening prayer before his message. In Braly Stadium (later on and for 17 years, the annual site of Division II National Championship football games.) There were probably six to eight thousand people there. I prayed. The governor spoke. Then, the two of us talked briefly with each other after the event concluded. To this day that was likely my biggest brush with fame, or infamy.

I am not sure I would have known the word then, but looking back ambivalence reigned in my soul. On the one hand, I wanted to represent Jesus and my campus group. I wanted to be a part of an effort to say that sex, drugs and some of the vulgarity making its way into rock and roll were not the answers for our generation. I wanted to stand up. On the other hand, Andrew Hairston’s exposition of scripture would not let go of me. That day Wallace, as I recall, stuck to his decency theme and stayed away from what people today call the racial “dog whistles,” but I could have completely missed those. This is I do remember: I had a good deal of uncomfortableness and angst (though I didn’t know that word then, either) about the whole experience.[2]

As time went on, I listened to the recording of Hairston’s Dallas speech and dug into the Scriptures. I came to new convictions about all kinds of matters to do with race and the Kingdom of God. I came to very much regret the vote I cast in the ’68 election and vowed to study the whole matter of voting and government involvement more deeply before I would again mark a ballot. But, more importantly, I came to the conviction that I must speak out. A year later in Memphis, Tennessee, as a theology graduate student and part-time campus minister, that opportunity would come, and speaking out would cost me my ministry job.

With all this, my relationship with my home state was becoming very complicated. Was I still thankful for my family? Sure. Was I still grateful for what God was doing even in Alabama? Absolutely. But was I getting my eyes opened? For sure. Was I getting a new view of defending my country? Indeed I was. Was I starting to see American history, racial relations, prejudice, and discrimination in a differently light? You know it. Was I proud of Alabama? No, actually that was slipping away. Was I starting to be embarrassed about being from my state? Yeah, that was becoming more and more true. And I was ashamed that I could have been so blind as to not see some things that should have been so obvious. Later on, of course, I would know this is just a part of maturing. But God was working on me. He still is. I have not arrived.

Why Alabama Tom?

All of this brings me to what caused me to do something that shocked even me, and that is decide I want you to know me as Alabama Tom Jones. After spending five decades trying to distance myself from my roots—from white supremacy, from Jim Crow, from lynching, from the Klan, from Governor Wallace, from blocking the school house door—I have decided for a number of reasons to put myself and my state in the same moniker… out there for all the world to see. And it is not because I think my state is now wonderful. No, it still has huge problems. Alabama may have as many politicians in jail as Illinois or Rhode Island. The governor in office as I write, stepped in when the former governor, and Baptist Sunday School teacher, resigned in the midst of a sex scandal. The previous Speaker of the Alabama House is serving a four-year prison term. It is not because my state still has a good football team and often has two. No, as I have grown older, that is not something I feel so proud about. I decided two years ago to not watch any football games that season. For that year I saw no football, college or pro, and didn’t see Bama win the National Championship on the last play of the game. But that is another story for another day.

So why would I attach my state to my name? Why make a big deal out of where I am from? I never have. Why now? Let me give you my reasons. But I am not guaranteeing they will make sense. This is a real “feeling” thing.

Reason #1

First, at this time in American history we are revisiting some of the ugliest parts of our past. We are still trying to come to grips with what Alabamian and former Secretary of State, Condelezza Rice, has called our nation’s birth defect, referring, of course, to slavery. Others have called it America’s original sin. We are more than 150 years removed from the end of the Civil War, but we deal everyday with issues from that time, and that is true both without and within the Body of Christ.

Racial relations have been worse in the past than now, or maybe we should say white people have treated black and brown people worse in the past. It does seem that we have made progress. Especially in some places in the church, it is a different world from the 1950s and 1960s, but underneath, there are still things hurting some people (of color) while others (who are white) are completely out of touch with that pain, and often out of touch with their own biases. There are still huge lessons to learn.

I have just recently been in meetings with faithful disciples where there were various painful racial overtones, poor word choices, judgments and misjudgments coming from our failure to understand each other or to deal with matters of the heart. Lesson learned: We have miles to go before we sleep. We are not yet healthy. Now is a time to speak. Alabama is, arguably, ground zero when it comes to racial tension and division and bad practices. If I am ever going to be Alabama Tom Jones, and face my past, it should be now. People like me need to be addressing these issues, sharing where we have come from and what Kingdom teaching has to say.

Reason #2

Second, none of us should try to hide our roots. I have made that mistake. Not a one of us had one word to say about where we were born or what color our skin would be. We did not get to pick the family we were in as children, or the city or the state or the country. People made fun of where Jesus was from, but there is no indication he was ashamed of his home or his origins. That didn’t mean he thought they were all just fine. He challenged them, even as he brought the fulfillment of the Kingdom right into their midst (Luke 4). They ultimately rejected him, but since we know he later wept over the same response in Jerusalem, he surely felt deeply for his own hometown and nowhere tried to distance himself from them. What I see is that we need to let the seeds of Kingdom love, redemption and transformation grow in the soil of our culture and experiences whatever they have been like. Our roots may be renowned or lowly, but we can be sure that no background was better than another in light of the Kingdom. All fall short. Wherever we came from, we all need redemption and transformation.

However, while we should not hide our roots, we should expose the darkness wherever it is found. I am deeply sorry about a lot of things that happened in Alabama. I am sorry for the horrible history of slavery that was in my state and many others. I am sorry for all the lives taken and the lives lost defending it. I am sorry for the awful years of white terrorism, lynching, Jim Crow laws, segregation and discrimination. I hate that it happened. I hate that I didn’t just hear about this. I lived through much of it and didn’t think anything about the suffering of African-Americans. I am sorry that I didn’t get to know them and that I joined the crowds in treating them like something less than we were.

I hate that four precious little girls were killed while attending Sunday School. The explosion at the 16th Street Baptist Church was caused by fifteen sticks of dynamite planted by Klansmen. I hate that men of my state committed that act of terrorism and brutality against other people of my state because they were a different color. It happened 125 miles from my home in a city I went to often. This violence against those girls happened only 1.6 miles from the stadium where I shouted “Roll Tide” on Saturdays. I am deeply sorry that for me and my family, it didn’t seem to matter. I recently checked it out: Those little girls died six days before my sixteenth birthday and probably all I was thinking about was getting my driver’s license the next week. I was a nice church-going boy completely absorbed in his own little world, and I am very sorry.

I am sorry for the firehoses and the dogs and that the Letter from the Birmingham Jail had to be written. I wish I could erase it all. I have had, and still have to, deal with white guilt. And it is not just because “my people” did that kind of thing, but that I was so out of touch and so complicit. I need to admit I was Alabama Tom Jones.

In the early 1960s while Birmingham was a place of pain and struggle for black Alabamians, it was for me the place where national championships were won (by all-white teams, by the way). I gloried in the latter and didn’t give any thought to the former. It would be more than thirty years later I would even know it was called “Bombingham.”

But I have learned that I can look back on the history of “my people” and I can condemn what they did, and what I did, without trying to hide where I am from. Wherever in the wide world you were born and grew up, bad things went on. Racial bias may have been institutionalized and weaponized in Nazi Germany, the American South and in South Africa, but you can be sure it exists everywhere. And if it doesn’t, you will certainly find other evils that are just as bad. Anne Lamont writes that a friend of hers says, “There are three things I cannot change: The past, the truth, and you.” While we cannot change the past or where we are from, we can certainly face the truth about it, learn and move forward in a better way. The point is not for us to be ashamed of our roots, but to show that we take the good we found there and, by the grace of God, overcome the evil we found there, letting the light into our souls right in those places or right in us wherever we have ended up.

Reason #3

That leads to the third reason I have decided to be Alabama Tom Jones. I want you to hear from at least some people from my state that the message of Jesus Christ can change even those of us from Alabama. They said about Jesus, “Can anything good come out of Nazareth?” I know people feel that way about Alabama. Hey, I sometimes feel that way myself. An editorial about my home state in the New York Times was published while I was first working on this. It was not complementary. It didn’t exactly ask, “Can anything good come out of that place?” but it made you wonder. (By the way, just so you know, I am not a New York Times basher.)

One day I started thinking that except for football glory and some things in the music scene, white people from Alabama don’t have a very inspiring history. We never had a Washington nor a Lincoln nor an Andrew Jackson (but he’s a mixed bag even though he’s on the twenty dollar bill.) Were it not for Helen Keller (from Tuscumbia, by the way) and a pretty long list of African-Americans, the state would not have a lot to celebrate. Thankfully, there are Booker T. Washington, George Washington Carver, Rosa Parks, Fred Shuutlesworth, Jesse Owens, Henry Aaron, Willie Mays and Condeleeza Rice. My Auburn friends would likely add Bo Jackson or maybe even Sir Charles (Barkley).

So, I looked at that and I thought maybe it is not too late to become Alabama Tom Jones. Maybe a white guy from Alabama could still inspire. But watch out, I told myself, because this is tricky. You could be on dangerous ground. Your motives had better be pure. You must not want this for personal glory. It must be because you want it known that the grace of God can reach even a self-righteous white Southerner, born and raised in the Heart of Dixie in white privilege (privilege he didn’t know for so long that he had) and believing in racial superiority. You must do it to point to the Jesus who opened your eyes to the evils of racism, white supremacy and bigotry that were in your own heart, and then, forgave you of all that and helped you catch a whole new vision of brotherhood in the new humanity he created. You must do it to show that through Jesus, something transformed can come out of Alabama…or Mississippi…or South Boston…or Germany…or South Africa.

You see, if I hide my Alabama roots you may never see that. And honestly if I am not transparent in this way, I myself may never see what a miracle God has performed. I may deceive myself into thinking I am some self-made man who extricated himself from a distorted view and now lives in a realm above my old Alabama neighbors.

Enter Mississippi John Hurt

Back some months ago I watched a documentary on PBS entitled “American Epic” that was about the birth of musical genres in the United States. It was in this program that I was introduced to the man known as Mississippi John Hurt. Quite unexpectedly I found myself being deeply touched by his story and persona.

John was a black man born in the tiny spot called Teoc and raised a few miles away in Avalon, Mississippi, another place you may not be able to find on a map today. He taught himself to play the guitar around age eight. As he worked as a sharecropper, he played music at dances and parties.

At age 36, John was living alone in his little three-room cabin, when he was discovered in 1928 by a record agent who led him to Memphis where his first recordings were made for Okeh Records. After the record was made, the company sent him a copy. but he had nothing to play it on. He took it to the white lady he worked for and asked if she had a Victrola. She cranked it up and let him stand outside the screen door and listen while she played his single.

The record was a good seller. Soon he would be asked to go to New York City for another recording session featuring one of his best tunes, “Candy Man.” Feeling lost and homesick while in the city, John wrote “Avalon Blues” which became another hit. His road to fame, however, was quickly interrupted by the onset of the Great Depression. Nothing more came of his efforts, at least for the next 35 years.

Until 1963, he lived back in obscurity in Avalon, minding someone else’s cows. He gave up the guitar. His music stopped. But then more than three decades after his first record, a blues enthusiast named Dick Spottswood searched to see if Mississippi John was still alive. He found him, still in his little house in Avalon. Spottswood loaned him a guitar and the magic came back.

Soon he had booked John as a last-minute replacement at the ’63 edition of the Newport Folk Festival. He hadn’t picked up a guitar in years, but at age 71, he began a three-year revival of his musical career that resulted in the recording of several albums. At age 74, he died in Grenada, Mississippi, 21 miles from Avalon. You can find his music on YouTube and his songs have been recorded by the likes of Bob Dylan, Jerry Garcia, Beck, Doc Watson, Taj Mahal, Bill Morrissey, Gillian Welch, Josh Ritter, and many others. Great blues artist Taj Mahal said, “John Hurt was like a man with the key to the musical universe.”

Why was I so moved by Mississippi John Hurt? Maybe it was his kind face and the humility and contentment he seemed to exude. Maybe it was the story of an amazing talent that only shined for five or six years in two different eras, but had great impact. Maybe it was the fact that John was a poor black man who touched the world, when he was the kind of person that I and my family would have avoided. Maybe it is because I’m 71 and Mississippi John was rediscovered and practically “reborn” at 71. Maybe it had something to do with the fact that the name of another place that doesn’t get good press was connected to an inspiring account. (I doubt I will ever again think of Mississippi without thinking of John Hurt. “Mississippi John” has replaced “Mississippi Burning.”).

And then, maybe it was the converging of all these things.

Who knows all the ways God’s Spirit works in us and on us? But this I know: Without Mississippi John Hurt, I don’t think I would have ever thought of being Alabama Tom Jones. Since going there has been very good for me, Mississippi John, I thank you. While I will never inspire others with my song writing or with great finger picking or with a smooth voice like you had, I am different because of you. You have helped me embrace my roots in a redemptive way. I don’t know much about your faith. I see you did a 78-rpm with “Blessed Be the Name” on one side and “Praying on the Old Camp Ground” on the other. However, I know God has used you to take me to some new places.

A Broad Redemption Indeed

I now know that I can give people of my state—both black and white—this word:

Whatever gifts you have or don’t have, because of Jesus, your heritage, your roots and even your religion can be redeemed. Because of a surrender to him, you can see the world in a different way and you can inspire others in ways you would hardly believe. I can be an Alabama Tom and you can be an Alabama Michael or Alabama Charlotte or an Alabama Desi. And in the process just maybe we can inspire others to be a New York Vincent or a Kansas Leslie, (although it won’t have the lyrical quality and charm of a Southern state!).

I hope you don’t misunderstand, but since this is such a “feeling” thing, you very well might. What you have read so far in this book and what you will read in the rest are not the words of a man once again proud to be a Southerner. They are the thoughts of a man, born white in Alabama, who was given the grace to see how much he needed grace. I write about the Kingdom of God not because I have it all figured out, but because the one who reigns in it has us all figured out and still loves us and draws us into it. Our heritage, our race, our roots, our politics, our religion, they can all deceive us and mislead us. But the prayer, “Your kingdom come; your will be done…” can guide us and lead us and transform our view of all those things and even make good use of them.

Not long ago, and I mean not long ago at all, I would have cringed at the idea of printing “Alabama Tom Jones” on anything. Now I have an overwhelming sense of not deserving to be Alabama Tom Jones. I am not sure you will understand that. I’m not even sure that I do. But, as I have moved into my seventies, I am more aware than I have ever been that I was lost and I now I am found. More than ever, I appreciate the words of another flawed Alabamian:

“Just like a blind man I wandered along

Worries and fears I claimed for my own

Then like the blind man that God gave back his sight

Praise the Lord – I saw the light.[3]

Jesus had a place-connected name. Today we gladly call him Jesus of Nazareth. Nazareth Jesus. So…Alabama Tom. Tennessee Reese. Florida Jeanie. Colombia Flavio. Louisiana Gordon. Wisconsin Clayton. Atlanta Steve. North Carolina Wyndham. Congo Titus. You get the idea.

All that we have been can be infused with all we can still be, and the transformation can be glorious. But it’s best if we tell the whole story from beginning to end. And for me that means being Alabama Tom Jones.

[1] I have written more extensively about the significance of this conference in my book In Search of a City: An Autobiographical Look at a Remarkable but Controversial Movement, pp. 17-21. This is now available also from Illumination Publishers at ipibooks.com.

[2] I must note a change in George Wallace’s life that is little known, or at least, seldom reported. After another presidential run, when Wallace had been paralyzed by an attempted assassination during the campaign he publicly apologized for his racism in a black church and asked forgiveness. It seems that playing a major role in his repentance was the compassion shown to him by New York’s Shirley Chisholm, the first black woman to ever run for president. Chisholm, who was running at the same time as Wallace, rejected the advice of her staff, suspended her campaign on the West coast and flew across the country to visit Wallace in the hospital. He was shocked and moved. Ten years later, after being out of office for six years, Wallace sought a fourth term as Alabama’s governor. The man once reviled in the black community, won a new term as governor, largely because he received 90% of the black vote. Thirty-seven years later, the May 16, 2019, edition of the Washington Post called George Wallace “a model for racial reconciliation.” https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2019/05/16/changed-minds-reconciliation-voices-movement-episode/?utm_term=.9fc6512639d1.

[3] From “I Saw the Light” by Hank Williams, written in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1947, the year of my birth. Not popular at first, this song would go on to become an American standard.