We all are different colors, aren’t we? People would say that I am a white person, but no one is really white when compared to a piece of copy paper. I may be light-skinned, but I’m technically not white-skinned. I do have some color in my pigmentation, thank you very much! The little song about all children being loved by God contains this phrase, “Red and yellow, black and white, they are precious in his sight.” This suggests that Native Americans may have a reddish tint in their skin color and Asians may have a yellowish tint in theirs. Black and white may seem self-explanatory, but almost unlimited variations of color are a part of these two basic shades. Why, then, are we different colors? It is primarily an issue of sunlight and vitamins – but keep reading! It is much, much more than chemistry.

Does It Matter?

Does it matter, the color of one’s skin? Yes and no – and both answers have a positive side and a negative side. Yes, it matters in ways that it shouldn’t. If skin color causes some people to feel superior or inferior to those of a different color, then that is bad, very bad. And we are dealing with more than the difference in what we call races. People of color, be they primarily brown or darker, can feel inferior or superior to those in their same race classification because they let color matter to them – different shades of color in this case. I have heard or read of those who felt that their particular skin shade was too black or too dark, and it is no secret that such variations make a difference with some. Lighter is generally considered better, and that is sad. It shouldn’t matter, but it sometimes does, to some at least.

On the positive side, it matters in a different way. If we view ourselves as God’s creation, we should be proud of our skin color. As the little boy in the old illustration purportedly said, “God made me and God don’t make no junk!” I’m not sure why he said that, but in spite of his grammar, his point was entirely correct. I have often said that I am not colorblind except in assessing the equal value of all people. Otherwise, my goal is to be color aware and color appreciative. After saying that in sermons, I have had black people thank me with tears in their eyes, saying that they don’t want their color to be discounted but rather valued. Saying you are colorblind may not be viewed positively, in spite of your intentions. I get it. We should be proud of who God made us, and that includes our color, our ethnicity, our gender and all else that makes us who we are as individuals.

Haters Gonna Hate!

Having said that, our color differences account for historical challenges beyond comprehension, especially in the United States. Our history of slavery in earlier days and all forms of racial oppression since has marked us as a society. We are working our way to better places, but right now we are in the midst of a very challenging place. A white person can lose their job or even their company (think pizza!) by using a racial slur publicly. Yet, racial tensions are the highest since the Civil Rights era a half-century ago. How does that happen?

It happens because human beings, the very apex of God’s creation, are a fallen people. The sins of Adam and Eve have carried consequences with them since the dawn of creation. We know how to love to an appreciable degree and we know how to hate to a similar degree. Our differences in every area are often the catalyst prompting that hate. We can tone the term down a bit and call it bias or prejudice, but it resides in every one of us in some way, often in ways of which we are not aware. It may be based on color differences, background differences, language differences, religious differences, educational differences, economic differences, nationality differences, political differences, gender differences, etc. The list of ways that our prejudices can manifest themselves are virtually endless.

I was attending a class on racial diversity a few months back, and after some US residents described the black and white challenges we experience in this country, an African man described similar challenges between different tribes in his country – where everyone in those tribes is black. Further, the dangers of being of a different tribe in the wrong place at the wrong time were greater in that country than being black or white in our country in the wrong place at the wrong time. It was a scary description, to put it mildly.

So what does this show? That haters are gonna hate! Listen to Paul describe our pre-Christian condition: “At one time we too were foolish, disobedient, deceived and enslaved by all kinds of passions and pleasures. We lived in malice and envy, being hated and hating one another” (Titus 3:3). Thankfully, he goes on in the next verses to describe the difference being in a relationship with Christ makes. This contrast explains why this blog is dedicated mainly to helping Christians deal with their sins, especially prejudices, including racial prejudices of which we may not be conscious (whether we are black or white or brown).

The world is going to hate – it always has and always will. Until and unless people accept Christ and his way of viewing others, people don’t change. Congress might legislate consequences for outward actions, but they cannot legislate the same for thoughts and attitudes. Society can only be changed in those areas one person at a time through Christ. Having said that, I do not believe that just because one becomes a Christian, some kind of magic eraser comes and deals with race and racial issues. We have further to go than we think in building true diversity in our church culture, which must encompass our attitudes and relationships inside and outside of our church assemblies.

Why Are We Different Colors?

We can probably all agree that this is a good question, even an important one. I believe that is hugely important, for it affects our view of God, the world and every person in it. No wonder Satan has worked so hard and so effectively to hide the truth from us! Hopefully the following explanations will help us in exchanging the mistaken parts of our views for God’s views regarding the answer to this question. I love the answers that I am writing about in this article, and I’m excited and elated to share them!

Answer #1 – The Nature of God

God is Creator, yes? As you look at his creation, what do you see – drabness, ugliness, boringness, monotonousness, dullness? That’s not what I see. I see amazing diversity in all of nature. How could God have stifled his creative genius and made everything look the same? Consider any part of creation and you will see diversity almost beyond human comprehension. Take the birds, for example. How many kinds and how many colors and how many shapes do you see? More than you can count. More than even an ornithologist can count, with all due respect to you birders out there. Take flowers, for another example. How many kinds, colors, shapes are in God’s creation? You can add for consideration trees, plants, grasses, cats, dogs, horses, cows, all types of wild animals. And what do you get? Diversity to what seems to us mortals the nth degree!

Now think about human beings, the crowning achievement of our Maker in exercising his marvelous creative abilities. Would it have not been astoundingly weird for him to have made us all look the same? All with the same skin color, eye color, height, bone structure, etc. etc.? Even a very small amount of common sense should tell us that the differences in humans, including skin color, are a logical necessity when God’s creative genius is taken into consideration. We should delight in human varieties as much (more actually) than we do in the other varieties in nature.

The idea of different races is a false concept, as we will show later in the article. But different ethnicities and cultures are a reality, and I rejoice over them. They give us so many different types of food, drink, music, dance, and so on. As a nation, the United States once took pride in being the melting pot of many nations. In retrospect, that viewpoint was far more restricted than our earlier forefathers realized, but that doesn’t devalue the concept as it relates to my point. However, we should be totally aware of the fact that most of the “melting” that went on during much of our national history consisted of white people. The story of how people of color, all colors, became a part of the process is, for the most part, a painful consideration. But I love the human diversity in our nation and I really love and cherish the diversity in our fellowship of churches. I just want to help broaden it from having diversity in our official church gatherings to having cultural diversity in more and more unofficial social gatherings and in our close friendships.

Answer #2 – The Purposes of God

God loves humans and wants us to be with him for eternity. Wow! Read that again and think about it. Lauren Daigle’s song title comes to mind immediately – “How Can It Be?” Yet, it is true that God loves us beyond our comprehension to grasp and does indeed want us with himself for eternity. In order for that to become a reality, we must be saved spiritually – forgiven of all of our sins through the sacrifice of Christ, redeemed by his blood. God “wants all people to be saved and to come to a knowledge of the truth” (1 Timothy 2:4).

If that is his ultimate desire and design for us humans, how does he go about accomplishing it? Actually, in many ways. Fundamental to our study in this article, one of those ways is tied inseparably to the concept of diversity. In an earlier blog post on this site, I wrote an article entitled, “The Theological Centrality of True Racial Diversity.” Here are a few excerpts from that article:

The greatest demonstration of Christ through his spiritual body, the church, in the first century was the ability to blend two cultures, Jew and Gentile, who absolutely hated one another. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to make the application that the ability to totally blend (not just mix a bit on Sunday morning) black and white cultures is the greatest possible demonstration of Jesus in our day. Further, if working out the kinks between two groups of Jewish culture in Acts 6 produced a response of converting large numbers (even priests), just what could happen if our movement led the way in having true spiritual diversity?

What is the biggest deterrent to love, unity and growth (spiritual and numerical)? Hate – Satan’s greatest tool to produce the kinds of horrific actions taking place in the world today and in world history. What is the greatest demonstration of love, unity and growth? Whatever defeats hate – the greatest kind of hate. Surely overcoming racism would be near or at the top of that list. So how did God choose to do that, thus setting up a demonstration that would have the potential to affect the world?

Easy answer: the Jew/Gentile form of racism and hatred. Hence, we are not surprised to read that the biggest threat to love and unity in the early church was how to get Jews and Gentiles into one family and to get them to understand, appreciate and love each other against all odds. God calls it his mystery to change the world. Read the following passages with this principle in mind: Ephesians 2:14-22; Ephesians 3:2-6; and, Colossians 1:24-27.

Bottom line, the more our goals on earth reflect our vision of heaven, the greater our fellowship will be and the more effective our evangelistic efforts will be. The church of the living God is the ultimate demonstration of Jesus and the heart of God, but it has to have as a major goal what Scripture defines as the mystery of Christ. One of my black reviewers made this observation: “I hope you can make people, especially the leaders, see how we have a field of dreams concept here with race. If we can be a light in dealing with racism, people will come to us.” In order for God’s kingdom in heaven to look like Revelation describes it, then we must pull out all of the stops to ensure that it looks like this in his kingdom on earth. God – open our eyes and hearts!

Revelation 7:9a

After this I looked, and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and before the Lamb.

Answer #3 – An Act of God’s Judgment

Thus far, we have introduced the subject and given the first two answers to the question posed in the title. Answer #1 talked about God’s obvious love of diversity in nature and the logical necessity of him creating the human race with the capability of developing similar diversity. Hence, it is something that shouldn’t make us afraid of one another, but highly appreciative of our variations. They are God-given and that makes them special indeed.

Answer #2 focused on the spiritual purposes of God through our diversity, notably bringing us all into one family, and through our relationships, showing the world the power of God to change lives. Just as Jew and Gentile were that divine demonstration in the early church, racial diversity in the church now is likewise designed to be that magnet that gains the world’s attention and draws them in. From here, answer #3 moves into some deep waters – in more than one sense. Read on.

The Bible contains many examples of God bringing judgment on mankind, be it on a single individual, a group within a nation, a whole nation or even the whole world. Besides those examples are warnings of judgments to come. The only example of the whole world being judged and punished was, of course, the flood of Noah’s day. The results of that flood were both immediate and long-term. The long-term results are the ones on which we will focus.

I understand that anything contained in Genesis 1-11 has come under increasing attack. Not only do unbelievers attack it, but many claiming to be Christians and Bible believers have ended up doing something similar. They have sought to reduce those chapters to mythology or something like it – anything other than reliable history in efforts to harmonize the Bible with modern science. When that seems impossible, the Bible is called into question rather than calling modern science into question. If that path weren’t so serious and didn’t carry so many implications that reflect on the rest of the Bible, I would find it quite humorous.

Modern Science, aka Current Science

Think about the term, “modern science” for a moment. What does that really mean? Only current science, that and nothing more. If you would like to release a few endorphins into your system through laughter, study the history of modern (meaning only current) science. Some of the most outlandish views imaginable about our universe in all its parts were held at given points in time, views that seemed to those “moderns” of that era to be absolute facts. Many false assumptions about the Bible were held because the evidence for proof had not been yet discovered, but in time many of those same assumptions were dispelled through later discoveries (especially in archeology). Whether a false assumption is disproved scientifically or not, the Bible is still the Bible and it unquestionably claims to be God’s inspired word. That’s always going to be good enough for me.

On the subject of modern science (which again can only be defined as current science), one of the areas that receives the most attention and the most funding is that of nutritional and medical science. Those related branches of science are funded by billions upon billions of dollars annually. Yet in our lifetimes, how many “truths” have been asserted only to be debunked later? If you pay too much attention to those areas of “modern” science, you are likely to develop paranoia. Drinking coffee is bad for you – no, it helps with dementia and other health threats! Drinking alcohol will kill you – no, not drinking alcohol may kill you and it will increase your odds of getting dementia significantly. Those illustrations were found in very recent reading, by the way, and scores of similar ones could be noted and quoted.

Noah’s Flood Literal?

My point is that current science is by nature pretty dogmatic and often wrong. It will label theories or working hypotheses as facts, and if Bible believers aren’t careful, they may be sucked into that whirlpool of arrogance and pride that is most often based on atheistic world-views. Thanks for listening to me vent a bit – I feel better! Back to the Noahic flood. That horrific destruction is a fact if the Bible is to be believed. If it is some sort of symbolic fable, by whatever term, the rest of the Bible becomes untrustworthy. Here are a few of the comments made in other parts of the Bible, in contrast to those who consider Noah a symbolic figure and the flood a symbolic event:

Isaiah 54:9

To me this is like the days of Noah, when I swore that the waters of Noah would never again cover the earth. So now I have sworn not to be angry with you, never to rebuke you again.

Ezekiel 14:20

as surely as I live, declares the Sovereign LORD, even if Noah, Daniel and Job were in it, they could save neither son nor daughter. They would save only themselves by their righteousness.

Matthew 24:37-39

As it was in the days of Noah, so it will be at the coming of the Son of Man. 38 For in the days before the flood, people were eating and drinking, marrying and giving in marriage, up to the day Noah entered the ark; 39 and they knew nothing about what would happen until the flood came and took them all away.

Hebrews 11:7

By faith Noah, when warned about things not yet seen, in holy fear built an ark to save his family. By his faith he condemned the world and became heir of the righteousness that is in keeping with faith.

1 Peter 3:20

to those who were disobedient long ago when God waited patiently in the days of Noah while the ark was being built. In it only a few people, eight in all, were saved through water,

2 Peter 2:5

if he did not spare the ancient world when he brought the flood on its ungodly people, but protected Noah, a preacher of righteousness, and seven others;

Of course, we could add in the mentions of Noah in both OT and NT genealogies, but you get the point. Both Noah and the flood are described as historical outside Genesis, and if they aren’t historical, then Jesus and the other writers of the Bible must have been hysterical or otherwise deluded. Some are tantalized by the discussion of whether the flood was local or universal. We don’t even know what the nature of the earth was back then, and how the continents may have been divided – or not. Feel free to read about the alleged Pangaea, or ancient super-continent, and later phases (Triassic, Jurassic, Cretaceous). Keep reading and you will find the hypothesis out there that most of the continents will combine once again into another super-continent, the Amasia. You might enjoy the reading, but please put your trust in the only book about which Jesus made this claim: “Heaven and earth will pass away, but my words will never pass away” (Matthew 24:35).

Honestly, I don’t have time for those views that Genesis is non-historical verbiage and I hope you don’t. I also hope you will speak up when otherwise respected people reduce those opening chapters of Genesis into something other than historical accounts. The so-called evidences of “modern” science that contradict the Bible are not my focus; the word of God decidedly is.

Two People and Eight People

In the beginning, there were two people – Adam and Eve. There were eight people who survived the flood and disembarked the ark. Surely I don’t need to multiply verses about what both OT and NT have to say about these facts and figures. As I was recently exiting a restaurant, I struck up a conversation with a black family sitting on a bench awaiting a table inside. As we talked about racial diversity (a subject I introduce as often as possible with as many people as feasible), the man in the family observed that we all got off the Big Boat together through our Noahic ancestors. Spot on! We did.

This means that we all started off appearing much more alike than we are today. So what happened to us? With some divine persuading, our forefathers finally were dispersed by God from the vicinity of their building project, the Tower of Babel,” (Genesis 11:8-9) into the locations he intended. Paul described it this way: “From one man he made all the nations, that they should inhabit the whole earth; and he marked out their appointed times in history and the boundaries of their lands” (Acts 17:26).

The fact that we all got off the ark together through our ancestors must mean that God created humans with a remarkable ability to adapt to our environments. And that innate capability explains quite simply why we are different colors. Yes, seriously. My good friend James Williams, a black brother in our church, spent his entire career teaching Social Studies to 8th grade students in his home state of Mississippi. He has said to me a number of times that our skin color and other physical characteristics trace directly back to the proximity of our ancient ancestors to the equator. The closer they were to the equator, the darker their skin. Not only is that a simple answer, it is absolutely accurate. Can it be proved? If you are a Bible believer, it has already been proved. Take a look at humanity in their native lands and there you have it. Oh, you want something from modern science (as we call it)? Okay, keep reading – and hold on to your seat!

Answer #4 – God, Anthropology and Chemistry

We have already covered three of our four answers to the question posed in the title. In the introduction to the series, I said that the answer in a scientific sense was essentially a matter of vitamins and sunlight. As strange as that may have sounded to you, reading this final answer should clear it all up. God’s design and creative genius is nothing short of astounding! Enjoy!

Now here is where the real fun starts. I love truth and therefore I love exploding myths! Race is a myth – there is no such thing. It is no more than a social construct based on ethnicity and culture. When I read Michael Burns’ excellent book, “Crossing the Line: Culture, Race and Kingdom,” many things caught my attention. One such thing really caught my attention, and that was the mention of a book by a well-known anthropologist. That anthropologist was Ashley Montagu, who in the same year I was born (1942) published a book entitled, “Man’s Most Dangerous Myth: the Fallacy of Race.” This stuck with me not only because the book was written in my birth year, but Ashley was my mother’s maiden name and further, the topic of the book was absolutely intriguing to me.

Montagu was quite the interesting character. He was Jewish, born in London and later naturalized as an American citizen. He was an atheist, and considering that he was born in 1905, I find it remarkable that he didn’t subscribe to Darwin’s views on race (described in his writings during the latter half of the 1800’s). Darwin believed that black people were much less evolved than white people, and as a result, less intelligent. Darwin also believed something similar about females generally, regardless of color. But Ashley rejected that part of Darwinism and along with Albert Einstein, spoke out strongly against the views and ill treatment of black Americans by white Americans. A part of that action no doubt came from their common Jewish backgrounds and the racism they had endured personally. But it was far more than that to Montagu – it was a matter of science. His views ended up pretty much carrying the day with his fellow anthropologists in rejecting any supposed scientific basis for race.

A Matter of Basic Chemistry

Recent anthropologists have continued to dig deeper into the complexities we call race, most often with an atheistic mindset. Nonetheless, their findings are remarkably helpful to those of us wanting to explain skin color differences. One of the big names in this endeavor is Nina Jablonski. She and her husband, George Chaplin, a geographic information systems specialist, formulated what was called the first comprehensive theory of skin color in the early part of this century. According to their theory, skin color is a matter of vitamins.

One article I read claimed that scientists have long assumed that humans evolved melanin, the main determinant of skin color, to absorb or disperse ultraviolet light. But why? The answer is turned out to be pretty simple. Two vitamins are the focus and the melanin in the outer layer of our skin worked over time to allow one type to be absorbed into the body and the other type to avoid being taken out of the body. Vitamin D must be absorbed in sufficient amounts to build calcium. In northern climates where the sunlight is less available, the skin must remain lighter in tone to make sure that enough Vitamin D is absorbed.

The other vitamin, called folate, a member of the vitamin B complex, is also essential to our health. Yet it is significantly affected by the ultraviolet light from the sun, dispersed from the body rather quickly if the skin is light. According to Jablonski, the body’s folate reserves can be cut in half within an hour if the sunlight is intense and the skin is very light colored. Hence, those in the tropics must have darker skin and the melanin takes care of that. Bottom line, if your ancient ancestors lived in low sunlight areas, they developed light skin; if they lived in high sunlight areas, they developed dark skin.

The only question mark I ran across among scientists regarding this now well-accepted theory was in considering the Inuit peoples whom we call Eskimos. They have dark skin and yet live in very low-light areas in the far north. Two theories are used to explain their aberration from the norm. One is that they migrated from hot climate locations and have not been in their new locations for long enough to adapt. The other explanation is that although they did migrate from somewhere in the tropics, they consume so much Vitamin D from their diet, especially blubber type fats which are rich in Vitamin D, that the skin color hasn’t needed to lighten up to receive more of this vitamin from the sun. Although the Eskimos give us an interesting exception to consider, they are an exception. The rest seems to be solid science and certainly accepted science. I’m aware that I’ve already made a point about current science not necessarily being absolute, but I feel pretty safe in accepting these current conclusions. At the least, they don’t contradict any biblical material, which was the main concern in my earlier comments regarding science.

Thus, my buddy James was right on target. The closer to the equator one’s ancient ancestors were located, the darker their skin. The further from the equator they were, the lighter their skin. Other physical characteristics, such as facial features, bone structure, hair texture and color would assumedly have developed similarly to best fit the environment.

A Mighty Thin Paint Job!

Nearly 40 years ago, I attended a couple of seminars conducted by a man in the Mainline Church of Christ named John Clayton. He had been a literal card-carrying atheist who had converted to Christianity. His seminars were about apologetics, the existence of God. I recall him greeting his old friends in attendance from his former association of atheists and then his newfound Christian friends. And then he got down to business and delivered powerful and compelling evidences for the existence of God. At some point, he dealt with race. He showed a picture of a black tribesman dressed only in a loin cloth. He gave us enough time to form our stereotypical opinions of what type person this was, and most of us likely thought of a very uneducated native from some remote tribe. Then he told us that the man was a PhD and one of the world’s foremost scientists in his chosen field. That was a valuable lesson never to be forgotten.

John also made a statement that I think I remember correctly, namely that the difference between the blackest black person and the whitest white person was 1/64th of an ounce of melanin. I do recall thinking, “Wow, that’s a mighty thin paint job!” How could so little of this chemical in our skin make so much difference in our world? A few months ago, when I was studying this topic, I wondered if Clayton were still alive (he’s older than me) and I looked him up on the web. I found an email address and emailed him to ask about that melanin statement.

To my amazement, he emailed me back quickly and said that he didn’t recall making the statement but that it sounded about right. He also said that he worked with John Oakes and Douglas Jacoby in the apologetics field and had kept up with my ministry through the years. God bless him! But why do we allow 1/64th of an ounce of anything affect our thinking about others who appear different than us? A sad part of the answer is how we judge appearance, how we judge beauty.

Au Natural and Proud of It

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, right? Partially right, but only partially. All human societies have accepted standards of what defines beauty. Those standards change in time and in cultures, but they are as real as the rain to the people in that culture. Since I relish diversity in general, I had to ponder the varying standards of how beauty is determined in different times and places. What I do not relish is when the standards of one culture dominate that judgment by becoming the standard for other cultures. You can probably guess where I’m about to go with this one, right?

What we call the Dark Ages was a period of time when less is known about civilizations that existed during those years. The term is often used synonymously with the Middle Ages, referring to the period of time between the fall of the Roman Empire and the beginning of the Renaissance or period of Enlightenment. The Enlightenment, also known as the Age of Reason, was a philosophical movement that took place primarily in Europe and, later, in North America, during the late 17th and early 18th century. Thus, this time of supposedly waking up to the finer things of life happened to be ushered in by white people.

Guess who decided which race was superior? Guess who decided how beauty was to be defined? I often refer to a comment in the Malcom X movie when he asked a black audience a question like this one: “Who told you that the color of your skin made you inferior? Who told you that the texture of your hair and your facial features were inferior?” His answer was obvious – white people! That is to me so very sad. Why would a woman with a narrow nose and small nostrils be more attractive than one with a broader nose and large nostrils? It’s all in the mind, but it is in the mind! By the way, I didn’t inherit one of those narrow pointy little noses myself. I remember the shock of seeing my nose in a mirror with a sideview option just after I had entered full-blown puberty! That prominent nose did help me develop a personality, however strange you think that personality might be! But you get the point.

Styles change in all sorts of areas – clothing styles, hair styles, and on goes the list. That’s all well and good. Save your out-of-style clothes – the cycle will most likely repeat. The part of style that concerns me is why we adopt certain styles or adapt to certain styles. It can be a matter of pride in trying to be a pace-setter or trying to keep up with the Jones (whoever they may be). It may also be a matter of feeling like we are inferior unless we adopt certain styles.

I know I can go over the line quickly here, so I will make it brief. I am glad that certain of my black sister friends are moving toward styling their hair “au natural” (a shout-out to Sharisse Lucas!). If women of color want to straighten their hair as a matter of personal preference, fine. Most of the women in my family do the opposite and get permanents (which are anything but, and not cheap). I just don’t want those of other ethnicities to feel the burden of trying to conform to what white people think is beauty. I’ll leave it at that and make one confession: I hope God lets me have an afro in heaven!

Enter the Geneticists

In time, scientists in other fields came to similar conclusions that the anthropologists had already reached. Those working with DNA are among those. In 2003, scientists completed the Human Genome Project, making it finally possible to examine human ancestry with genetics. I read an interesting article online from Harvard’s Graduate School of Arts of Science website. It was written April 17, 2017 by Vivian Chou and entitled, “How Science and Genetics are Reshaping the Race Debate of the 21st Century.” Under the subheading, “New findings in genetics tear down old ideas about race,” the following statement was made: “Ultimately, there is so much ambiguity between the races, and so much variation within them, that two people of European descent may be more genetically similar to an Asian person than they are to each other.”

I have watched You Tube presentations from college classroom settings demonstrating the same thing. You can observe a racially diverse group of college students comparing their DNA sequence to one another’s and see precisely the same conclusions. Our DNA simply doesn’t offer scientific proof of what we call racial differences. As Montagu said 75 years ago, our concept of race is a fallacy and a dangerous myth. It is beyond amazing that such a fallacious myth continues to prevail in our otherwise educated world.

May this article help even a tiny bit to dispel the myths perpetrated by Satan through the ignorance and biases of humans. Enough is enough! God made us all and he doesn’t make junk, as the little boy supposedly said. We are made in the image of our Creator, having the capacity to do amazing things as earthly humans and the spiritual capacity to live forever with him, the angels and all of the redeemed. May he help us to not simply accept our physical differences but to rejoice in them. And remember that even if someone thinks you are one of the “beautiful people,” as others would describe you, before you know it you will be old and wrinkled like me! “Charm is deceptive, and beauty is fleeting; but a woman who fears the LORD is to be praised“ (Proverbs 31:30). The only true beauty is that which resides within us, the spirit God placed in this temporary earthly tent we call the body. Focus on the right things and rejoice in the right things. God bless our diversity! It is his delight and must become ours!

Nineteen years ago, the world lost one of God’s finest — Arthur Conard. He and I, along with five others, were a part of a very special club. Its development and function just sort of happened, in what became a beautiful thing, a “God thing.” We were all members of the same church in Boston, a big family with great diversity in the membership.

I wrote this article quite a number of years ago, and it can be found also on my regular Bible teaching website (gordonferguson.org). I am posting it here in memory and honor of my special departed friend, Arthur, and to encourage his widow, Joyce Conard. I was privileged to be the officiating minister at his memorial, attended by more than 700 people. His aunt, who was not a member of our church, read the obituary details. She knew more about our club than I would have expected, for she stated that Arthur was a member of the “infamous” Big Black Brother’s Club! Read on and you will understand why!

You are all sons of God through faith in Christ Jesus, for all of you who were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ. There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus (Galatians 3:26-28).

Spiritual thinking means that we are colorblind in one sense, but it means more than that. It also means that we are both color-aware and color-appreciative. The Galatians passage above affirms that in some sense, physical distinctions are ended in Christ. Regardless of race, social status or gender, we are all equally valuable to our Creator. None is superior and none is inferior, for we are all made in the image of God and saved by the blood of Jesus. But we do not cease to be who we are racially, socially and sexually. Men are still men and women are still women. We must remain aware of those differences if we are to be effective evangelistically. Read Paul’s comments in 1 Corinthians 9:19-23 on the principle of becoming all things to all men to reach as many as possible.

We must also be appreciative of the differences that remain. America is a blending of cultures like few other countries. Of course, in our cosmopolitan world, the cultural and racial composition of most nations is far more varied than in the past. However, Americans generally relish the variations more than the norm, since we were built with this diversity from the beginning. We are the big melting pot, and the acceptance of this diversity is at least a part of the reason many from other countries would like to migrate here. The attraction of financial opportunities is the biggest draw, but even more because these opportunities are found in a setting where backgrounds don’t mean too much.

However, in spite of this relatively accepting atmosphere, prejudices abound. I was raised in a part of America at a time when blacks and whites were quite segregated. I did not attend school with blacks until post-graduate studies when I trained as a minister. (Thankfully, that all seems so strange now.) When I was a teen, I did construction work in the summers as what was called a common laborer, and most in that category were black workers. Being around black men on the job was the first time I was able to closely associate with them on a peer basis, and frankly, both they and I loved it. We had a blast acting more than a little crazy together. I enjoyed their fun-loving ways no end, and my life was enriched by close association with those who were different from me racially and culturally. Since I was a young adult, some of my closest friends have been from different minorities. As I learned from their cultures and backgrounds, I grew to delight in our differences.

The church in the Bible was made up of equals, but equals with some pretty significant differences. Learning to love each other and live together in one Body was not always easy, but it will always be God’s way. All white churches or all black churches or all Asian churches or all Hispanic churches stand in stark contrast to the early church that Jesus built. Variety is the spice of life. We need each other, and we need to be enriched by the differences in each other. I rejoice in the true kingdom of God, because it is such a conglomeration of different types of people. We have the rich and the poor; the educated and the uneducated; the young and the old; the social adept and what the world might call the social misfits; the blacks, the whites, the Asians and the Hispanics, and then mixtures of all of these. We are the same in heart and purpose, but not the same in so many other ways, and these differences are cause to rejoice. Only God could bring such a group together in love and harmony. Our unity is the demonstration to the world that we are true disciples of Jesus (John 13:34-35; 17:20-23).

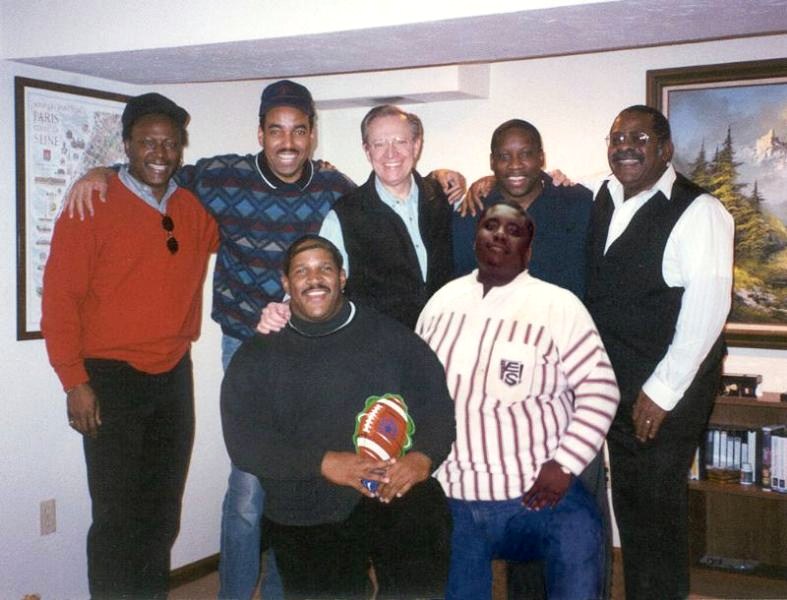

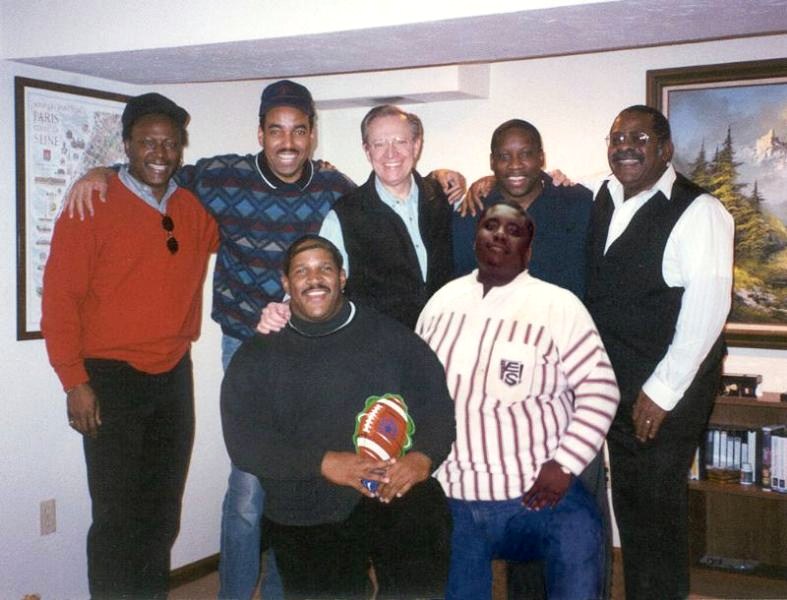

On my desk is a very unusual picture of seven men, affectionately called the BBB Club ─ the Big Black Brother’s Club. A number of years ago, several brothers in the church started coming over to our house on select Monday nights during the fall to watch Monday Night Football on TV. Most of these brothers were black, and gradually, the moniker of “the BBB’s” started being used. So, by mutual agreement, I was also black on Monday nights. (Actually, I always thought that I had too much soul to be a white man anyway!) On the nights when we are going to meet, we would discuss whether to invite a “token white” for the evening (remember, I’m black on Mondays). It was quite a group. Although a number of different “brother-brothers” (black disciples) have attended at different times, our club ended up with seven members: Bob Peterson, Walter Parrish, Curt Garner, Keith Avery, Jon Williams, Arthur Conard and me. My wife said that she could hear us out in the street, even though we met in the basement. Gin Rummy or Spades card games often competed with the football game, and to say that it was a lively meeting would downplay the true nature of the atmosphere considerably.

These brothers seemed to understand that I needed some setting where I don’t have to be a church leader of any type, but only one of the brothers, able to let my hair (what I have left) down completely. I needed these men and I cherished our times together. Now that others have heard about us, they are clamoring to get into the fray. With good-natured but raucous humor, we give them a hard time and let them know, that according to our by-laws, visitors have to be approved by a majority of the club members. None of those little white skinny guys have much of a chance of approval! Actually, those who do come have a great chance of losing their skinniness, since the food items are not exactly of the low-fat variety!

The picture to which I referred earlier is very unusual because it was taken after Arthur died suddenly of heart arrest last fall at age 38. (With the help of a friend, Arthur’s picture was scanned into a computer along with our picture taken later, and now we have the seven originals in a BBB Club picture.) He had a heart condition and realized that he would not live a normal life span. Yet he was as full of zest for life as anyone I have ever known. Deeply in love with God and people, he spent his last hours out sharing his faith. Returning home on the bus, he simply went to sleep and woke up with God. About 700 people attended his memorial service from all walks of life. The BBB’s, along with several of Arthur’s closest brothers wept together at his casket, but during the day, laughed about as often as we cried. Our tears were not for him but for ourselves. He will be missed greatly by his faithful wife, Joyce, and by a vast throng of friends and family who loved him deeply. Life for us will not be the same, both because he leaves a void and because he changed us by his copious love and laughter. My background was about as different from Arthur’s as one could imagine, but we were (are) brothers, and on Monday night, brother-brothers.

In our racially tense society, people are more than impressed at our camaraderie and deeply appreciated love for one another. Where else can you find such outside the family of God? We are in no way up-tight about our differences; we glory in them. God made us as we are and he expects us to enjoy each other to the full. Any family in which all the children were exactly alike would be boring at best. The diversity of nature demonstrates God’s belief in the special place of variety in his plans. When visiting our son and his family in Hawaii, I usually go snorkeling at least once. The numbers of fish species I see is astounding. It is often claimed that no two snowflakes are alike. (Of course, those making the claim must have done a rather enormous amount of research, and they will have to be satisfied with tentative conclusions at most.) God obviously is trying to tell us something important, even by the design of nature.

Spiritual thinking is colorblind in its absence of prejudice, but color-aware and color-appreciative in making us a family. I have often said that the ultimate effectiveness of spiritual leaders is found in their ability to lead different types of people. If we can only relate well or become emotionally close to people like us, we are missing out on one of the greatest possible blessings of life. May God grant you the perspective of family that he has taught the BBB’s, for then your life will be enriched more than you can imagine! And thank you, my unique brothers of the club, for allowing me to be one of you in far more ways than simply being members of the same church. Praise God for his plan for his kingdom!

Family, we need to talk. This won’t take long but it is important. I’ll be brief and try to avoid that lecturing tone that no one appreciates.

In the early 20th century, Swiss psychologist Hermann Rorschach developed the famous inkblot test, which soared in popularity in the 1960’s. Supporters of this test claim that when subjects are shown specific inkblots and name the first thing that pops into their mind as they attempt to identify the shape they see, it reveals much about their personality and emotional functioning. In short, just a quick glance can make known a person’s true identity and many other things about them. Whether that works in the field of psychology has been the subject of much debate in the ensuing decades.

But our society seems to be devolving into a Rorschach mentality. We see one image, one short video clip, one Tweet, one soundbite, one quote and we know all we need to know. Within a moment we know the truth of a situation and can safely jump to judgment. She is evil. He is a thug. She is a moron. He is a bigot.

A Case in Point

This has become the norm. This was proven again with the recent flap over the Covington Catholic school boys in Washington DC. One picture circulated the web, and everyone knew exactly what was going on. Within hours the young man’s face was spread around the globe and he was found guilty in the Rorschach test of public opinion. Twitter had spoken; this was worthy of being covered as global news. It was seized upon and pushed by a media that is desperately playing to the pay-for-clicks reality of their profession, and so will thrust forward any headline that sounds sensational and will satisfy the appetite of a society that feeds on the confirmation bias of stories that support what they already wish to believe. Yes, we have become a society that sees what we believe—even if it’s not there.

Let me tell you what I’m not doing. I’m not taking the side of anyone in this incident. This is not even about that incident. The Covington controversy is just another example in a disturbing trend. I’m not telling you what to feel, and you may feel a lot in cases like this. I’m not saying that we should not stand up to injustice or unfair treatment when we see it.

What I am saying is that as Christians we must let our minds and actions be trained by the word of God and not by the society around us. Were the young Catholic boys guilty and deserving of public shame? Were they guilty of everything they were initially accused of? It certainly seems now that the situation was much more complex than first thought. Just as many rushed to demonize them, it is true that many rushed in to defend them before they knew all the facts. I must also admit that these young men were given the benefit of the doubt by many people much quicker than if it was a different group of young men in their shoes. But how others would or would not have been treated in a similar situation is not the point either.

It’s Not Just the World’s Problem

What I’m talking about here is the rush to judgment and punishment. Before we even know the facts, the verdict was in. It was decided by many that their lives should be ruined. Sadly, we can’t just pin this one on the “world.” I went on social media and saw numerous examples of disciples of Jesus Christ from across the country spreading this story and calling the young man from Covington Catholic, “disgusting,” “horrible,” “racist,” “atrocious,” and more. (Let me point out that while this incident is an American controversy, this is not just an American issue.)

It would seem that Christians often jump to judgment as quickly as the world does. These young men were tried in the court of public opinion and many of us piled on because something in the story triggered us. Those triggers may be real, but does that give us the right to behave like the world around us? Others may have been unjustly treated in the same manner or far worse in the past. Okay, but does that justify ungodly behavior now? Those boys were insensitive or displaying bigotry. Maybe, but does that behavior now push someone outside of the bounds of God’s mercy and love or is it okay to judge and hate in that situation because you’ve “seen that look before.”

Let’s slow down for a moment. Now, I know not all of us are guilty of doing this. It’s safe to say that most of us are not guilty. But we cannot pretend that this proclivity to rush to judgment is not a problem in the body of Christ.

As is often the case, more information came in and indeed things do seem a little more complicated than first thought. It was a chaotic situation and there is likely plenty of blame to go around to everyone involved. That’s not always the case, but it was in this situation. There, are many times when people have prejudged a person or situation, ruined their lives, and then cared very little when the facts turned out differently than initially thought.

My point is not to get into the complicated details of any one situation. The details of this case and which side subsequently rushed to judgment are frankly irrelevant. I could easily offer less controversial examples to make the case. Just this morning, a picture of LeBron James sitting on the end of the bench alone during a game with a three-chair gap between himself and the next teammate was all we needed. Within hours, the picture was everywhere. LeBron is hated by his teammates. I’ve already seen at least four news stories this morning on that picture and observed it having been shared on social media by at least a dozen people that I know. Never mind that LeBron has a special padded chair for previous injuries that sits at the end of the bench, or that a teammate was sitting next to him but was checking into the game. Never mind that just a few minutes later, teammates were next to him. A narrative was created around one still shot and the Rorschach mentality was in full effect. This is a trend in our culture that we as disciples seem to be slowly allowing to creep into our own hearts.

And that’s my concern; that many Christians have seemingly embraced the emotional Rorschach effect that has gripped much of the world.

Are We Still Listening to the Bible?

Have we forgotten that Proverbs 18:17 guides us that the first one to state their case seems right, until someone else comes forward with another viewpoint? Have we minimized the call to be ministers of reconciliation? Have we failed to come to grips with the truth that “the one who has shown no mercy will be judged without mercy? Mercy triumphs over judgment” (James 2:13 ISV).

Have we lost sight of 1 Peter 1:13 (ISV) which says, “Therefore, prepare your minds for action, keep a clear head, and set your hope completely on the grace to be given you when Jesus, the Messiah, is revealed.”?

Peter suggests three important reactions that should be practiced by followers of Christ until it becomes habitual. First, he says, prepare you minds for action. Don’t get taken off guard. Things will happen unexpectedly. Seemingly shocking things will come across your screen. Will you fly off the handle or have you trained yourself to respond in a thoughtful and kingdom-focused manner?

Second, keep a clear head. Don’t get swept along by the emotional outrage culture of today. Train yourself to look at things from the viewpoint of the resurrection rather than those whose hope is rooted solely in what they perceive as justice and comfort in the present age. Being called to love your enemies, for example, means that there are bigger things at play than just giving into anger and disgust at those who we feel deserve it. And by the way, it is never okay, for a Christian to pile on in attempts to destroy someone because we disagree with them. Jesus called for Roman soldiers who were humiliating and oppressing fellow Jews to be treated better than that (Matthew 5:41).

Finally, he says, set your hope completely on the grace given to us in Jesus and the coming resurrection. That must be our focus. The world has different priorities. The priority of disciples is to demonstrate the kingdom of God in every action we take, every word we say, and every post we make. If our responses look and sound just like the world’s, then where is the alternative hope of God’s kingdom? We’ve all flown off the handle before and responded emotionally at times, God knows I have. But we’ve got to do better. We must strive to display God’s kingdom and not our emotions or preferences. That doesn’t mean that we don’t ever confront injustice or evil. That’s not what this is about. This is about the rush to judgment and our role in the world as image bearers.

The next time we see one of these controversial stories in the news, let’s take Peter’s advice. Be prepared for this. Keep our heads. And carefully and prayerfully think about how we can display the kingdom of God to all sides and not just become a water carrier for the various non-kingdom agendas of the world. Let’s put down the Rorschach mentality and pick up God’s word to let it guide us.

When I first started writing my blog, I entitled it “Black Tax and White Privilege.” I found out quickly that the term “white privilege” was a loaded term, for it elicited some very strong negative responses by white people. I didn’t mind the strong responses and tried reasoning with some of those who wrote them – pretty much to no avail.

Then I read what my trusted fellow Bible teacher and author wrote in his tremendous book, “Crossing the Line: Culture, Race and Kingdom.” In chapter 17 of the book, a chapter entitled “Forging Ahead,” he advised against saying certain things and using certain terms, white privilege being one of them. Here are his comments in that regard:

Don’t use the term “white privilege.” This is another hot-button phrase. I don’t believe it is helpful, though, because it is usually misunderstood, and it tends to shut down conversations. The phrase refers to the fact that society was built on the assumption that the white culture, and by default, white people are the norm for behavior. It doesn’t mean that all white people are rich or have had everything given to them. It means that they will typically receive the benefit of the doubt and will be accepted and understood wherever they go. It means that their skin color is not going to immediately cast them into a negative light or stereotype. I have come to understand the truth of this. As I have said previously, I can do things in this country that my black sons cannot. I get the benefit of the doubt in many situations that they do not. It does not mean that they cannot overcome those things, but that they need to overcome certain things that I never had to deal with.

Because the term is so misunderstood, though, I recommend finding other ways to express the truths behind it without using that specific phrase. When you use it, you might be referring to the privilege of coming from the dominant culture, but people will think you mean something else and become defensive. Using the term “white privilege” just leads to confusion and often elicits a negative response at this point.

After reading this, I talked to Michael and he suggested that I change the title of my blog to Black Tax and White Benefits,” which I promptly did. The other term is not just explosive to some, it is that because it is so connected to the sordid world of present politics. Being apolitical, I don’t want to enter the shifting sands of politics per se and detract from my real purpose. That being said, after reading Steve Hiddleson’s post on Facebook first thing this morning while still in bed trying to wake up, I couldn’t help feeling compelled to write an explanatory article about what white privilege really is. Before including Steve’s post, let me explain who the Hiddlesons are.

Steve and Keri Hiddleson

Steve and Keri lead a region in the Phoenix Church of Christ, a region Theresa and I once led and then remained members of when they started leading it. They are some of the finest Christians I have ever known. They are very dear personal friends whom I consider my spiritual children. I was present when they adopted Nylah (as was half the church!) nine years ago. She and her two sisters are wonderful young women. But this morning, my heart was broken as I read the following post by Steve.

Dear fellow White People. We have a ways to go my friends. I was doing a paper recently and read a recent Harvard Business School Study that showed that resumes with “white” names are twice as likely to get calls for interviews than the same exact resume with a “black name”. Huh? Some black graduates are therefore choosing to “whiten” their resumes to get calls for interviews. This week my child was called a gorilla by a fellow student. No words…How does a parent heal that comment? My hope is that the other child innocently spoke out of ignorance and a lack of exposure to being around black people, and not out of a mean spirit. There is too much of both the former and the latter. A rich and famous black athlete recently said (after receiving some choice racist slurs slung at him) that being black in America is tough. I’m getting better understanding of that. I hope we all are.

Why I Teach and Write on Racial Issues

Here was my initial response to the Facebook post: “So sorry, my friends! Given that your family is one of the closest on earth to my family, my choice to speak and write about racial issues is far more than an academic endeavor. One explanation of the term “white privilege,” admittedly a misunderstood and controversial one, is that white kids will typically not have to face what your daughter will. But Christ will make the difference as she handles the sickness in our society. Thank God for the church! I love you!

I think that was a good initial response, but I must say more. I just returned home last night about midnight (delayed flight) after teaching and preaching in Knoxville, Tennessee over the weekend. I conducted a workshop Saturday on the topics of race and gender, and then preached on Sunday. This church is a bit unique in that it has a predominantly white membership and is led by an African American couple – Anton and Sharon Ivy. I was very encouraged by the church and their openness to learn more about two very important and very sensitive topics. It was in my estimation a great weekend.

One sister there asked me a question that ties right into this article. She was sincere, sensitive and had not a hint of any racist attitudes. Being raised very poor economically, she wondered how the term white privilege could possibly apply to her when she was growing up. I explained what was made clearer in Steve’s post and in Michael’s book. White privilege is not so much what you have; it is what you don’t have – stereotypical treatment of the worst kind. A fairly recent segment of “Dr. Phil” was devoted to showing what white privilege is. He is quite in tune with the topic, as were his panelists. As Michael Burns puts it: “White privilege does not mean that you did not have obstacles and challenges in life; it means that your skin color or culture wasn’t one of them.” That’s the bottom-line issue.

Opps – Sorry, Officer!

In my sermon yesterday, I used an illustration about being stopped by a white policeman in East Texas last year for a “rolling stop” at a stop sign. I tried hard to talk the officer out of giving me a ticket. It wasn’t so much about the money; it was about my previously clean record: no tickets for moving violations in 60 years of licensed driving. So I pled my case, to the point that my wife thought I had crossed the line of common sense by a wide margin! I didn’t succeed and paid my $200 fine and an extra $60 to keep it off my record. I felt comfortable giving the seemingly nice cop a hard time.

However, if my skin had been black (especially in that rural East Texas setting), I would have responded the way that all black parents teach their children to respond in similar circumstances. I would have kept both hands on the steering wheel, spoke as respectfully as possible with plenty of “Yes Sir” and “No Sir” comments in the mix and probably would have thanked him as he handed me the ticket. You think I am being overly dramatic here? Ask your black friends about what I am saying! Or come visit East Texas where Confederate flags still fly!

By the way, I have been accused of stereotyping law enforcement officers by using illustrations like this one. That is certainly not my intent. I have brothers and sisters in Christ, black and white, male and female, who are law officers. I also believe that the majority of white officers are good people, like the one who gave me that ticket. But I also know that there are enough of the other type out there to keep black folks from feeling safe with the police, and I understand why.

Let’s Get Real!

That was an example of what I mean by white privilege. I don’t get pulled over for DWB (driving while black) in a predominantly white neighborhood. A large percentage of my black friends have, especially the males. My children didn’t have racial epithets hurled at them when they were nine years old. People don’t look at me oddly when they hear either my first or last name, because both are, you know, quite “American” (white American)! I apologize for my edginess this morning. I’m just hurting for my little friend Nylah and her family.

I don’t pretend to think that our broken society in America is going to be racially healed anytime soon. The world is the world is the world. It always has been and always will be broken in one serious way or another. We are as a society more sensitized about racial issues than ever and yet racial tensions are at the highest point since the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. And this is in spite of the fact that using one racial slur can cost you your job, your career, or your company.

This sensitization, combined even with legislation, may limit overt racism but it cannot eliminate it in the heart. Volatile actions and reactions are going in all directions, stirring up more and more of the same. Some of those who bemoan the fact that some younger people are being radicalized by Muslim extremists are radicalizing their own children in the racial realm. Just last week, a black disciple posted that her child was told by a white classmate that “black people should die because their skin is different.” Both children are six years of age. The only thing that can heal us is love, love of the type that only comes from imitating Jesus with his Spirit helping us to do so. Nothing short of that is going to change our world, but we in the family of God can make sure that we are both loving and informed. Let’s love Christ, live Christ and preach Christ. To that end, I write…

My experience with racism and prejudice

I recently discovered that my adopted 9-year-old Sudanese-American daughter had been called a “gorilla” at school. It broke my heart. Trying to assume the best of people (especially young kids), I got the impression that the boy who said this spoke out of ignorance and not out of hate. That kind of comment still hits a young child’s heart in a bad way and will have a cumulative effect over time as ignorance and hate express themselves. I posted the experience from a father’s point of view on Facebook and the response has been pretty intense. One response that prompts me to write some more on this topic was this comment by a sister in Christ: “I wish more Caucasians would speak up on this issue.” OK. I’ll speak up some more. I’d be glad to. Maybe others will too! As a white guy I sometimes think, “Do I have the right to speak on this issue?” Apparently, I don’t just have the right, but my brothers and sisters want me to speak up! Here goes.

Whiteness in Sunny California

I was raised in Sunnyvale, California for 18 years. Great town. Great schools, parks, sports, and a low crime rate. Middle Class through and through. Nearby towns of Palo Alto, Los Altos, Cupertino, and Los Gatos were even nicer, so somehow I felt like we were “blessed” but that others had it better. Having lived in various places across the US since, my understanding has changed. We had it “really good.” Those nearby places were really rich, and we were just less rich.

I had cognitive dissonance at my elementary school, however. That’s a fancy phrase for saying, “I was uncomfortable in a confused kind of way.” I loved school, particularly for the opportunity to play sports at recess with friends, and at PE time. I did well in class, for that was the expectation, but sitting still was not my thing. At recess time (they had a lot of recess in those days) we all got out there. We competed in everything from soccer, to kick ball, to tether ball, to basketball, and football. Now here’s where I felt uncomfortable-in-a-confused-kind-of-way: At recess I looked out on the hundreds of kids playing and I only saw one black person, Mike Davis. One. Out of hundreds of kids. I’d estimate 8-10 Latinos, maybe, attended the school, but my memory is not as exact on that front.

But when there is “one” and only “one” African-American, well that’s kind of noticeable. And, it was kind of disturbing for a little kid. Why is there just one? The teachers are nice, the people are nice; what’s wrong with this school that we have just one black student here? I knew as a youngster that there were many more white people than black people in the US. I also knew that people attended school based on their neighborhoods, so that meant there was likely one black family in all of the surrounding neighborhoods near the school. One. “What does this mean?” I asked myself. Here is my childhood reasoning regarding the possibilities for this discrepancy:

- Black people are afraid to live in these neighborhoods with all us white people. Or they just don’t want to. Or maybe white people don’t want them to. If so, that’s not cool.

- Black people can’t afford to live in these neighborhoods with us white people. If so, that’s not cool. Why wouldn’t they have just as good of jobs as white people? The San Francisco Forty-Niner Willie Harper moved into a neighborhood near our school a little later. Does a black person have to be a pro athlete to live in this neighborhood? What’s going on? This is crazy.

- I’m no expert, but I got the strong feeling that the fault for this lies with the white men that came before me. Something got screwed up. The show “Roots” came out when I was 7. I watched some of it. I started to put two and two together on how “that” still affects us today. I got this feeling in my gut that my ancestors screwed something up and that maybe I might need to be part of some solution in the future. It seemed to me that if the white people broke something then maybe the white people ought to fix it. Common sense is easier when we’re 7, ya know?

One Black Friend

For good or for bad, those were the thoughts of a childhood boy in the burbs. Now here’s the only cool part of this chapter. Mike was awesome. Mike played sports with us and we had a great time! I never saw him made fun of or excluded in 4 years together at that school. (I’m not saying it didn’t happen, but I didn’t see it.) Mike was one of the guys. It felt right to have a black friend. America is a melting pot, so shouldn’t we be melted together? It just didn’t feel right that there wasn’t more diversity. It felt like there were forces at play that were dark in nature. Exclusive in nature.

Recently, I got in contact with Mike Davis through Facebook. I was super eager to know “what he felt” in our 99% white community growing up. I asked Mike, “remember me?” He said, “You are the guy I threw my only touchdown pass to in the 5th grade!” Well, I was taller than everyone else! We had a good chat and I asked him straightforwardly about how he felt being the lone black kid on the playground and if he experienced grief and a feeling of exclusion or separateness because of it. He told me that he had a good experience in elementary school, and can’t recall anything negative there, but that the racial stuff hit later on in middle school. It was great to catch up with him and hear that he is doing well in life. It was sad to hear that racial hurt began in middle school.

Well, knowing Mike was a blessing as a kid. I knew one black guy, and he was great! But the fact that I knew only one black guy haunted me. What was the reason for this? My middle school experience was much more diverse, thank heaven. Truth be told, a rival middle school was closed and the two were merged. For the first time I experienced sitting behind Jerry Curls dripping on Members-Only jackets, break-dancing on cardboard, and a host of other wonderful cultural experiences. Now this was living! I loved my more-diverse middle school! It still wasn’t as integrated as it could have been, but what an improvement!

Alas, with re-drawn lines for high school, I went to a mostly white school with some Asians, a few Latinos and an extremely few blacks in one of those “nicer-than-ours” cities. It was a good school but that uncomfortable-confused feeling returned. Why aren’t there more Latino and black families in this neighborhood? Are blacks and Latinos excluded in the marketplace from getting good enough jobs to afford this neighborhood? If so, that’s messed up! What’s going on in my society?

God in a Black Brother

Fast forward to UCLA in 1990. I’m in a fraternity with mostly white kids (I joined to impress my girlfriend at the time). In my pledge class we had a great young black student. I believe there were one or two more in the whole fraternity, so 2-3 out of 120 or so guys. Spiritually, I began to seek God. I became a Study of Religion major in hopes of finding God. A young black student my age (Darius Simmons) tapped me on the shoulder and invited me to a Bible study group at his place. At that moment, my life was about to change. I would go on to study the Bible with him and become a Christian. Everything I’ve done since that meeting was completely affected by that one pivotal moment in time. Here are the thoughts that I can reconstruct at that very pivotal moment about Darius:

- You are friendly. I like your spirit.

- You seem like you have a strong faith. I’m impressed. My faith stinks right now, and I could use some help. You are offering to help me? Thank you! I can’t believe you just walked up to a stranger and shared about God. I’d be terrified to do that.

- You are black. I’d love to learn from a black person. I’m still confused about how black people seem to be so excluded in so many ways in our society. Maybe you could help me figure that out. You want to be friends with a white guy? Are you sure? I’m glad you’re black. Let’s do this. I’m guessing you’ve overcome some things in your life based on your race. I need some help overcoming a bunch of stuff in mine.

Darius was used by God to save my soul, and we remain good friends to this day. Praise God for the inter-racial fellowship I became a part of there at UCLA. I briefly had an inter-racial relationship (boyfriend-girlfriend) that I won’t go into but suffice it to say we had some very painful experiences. We broke up for spiritual incompatibility, not racial issues, and remain friends in the fellowship. Neither of us would have backed off the relationship for racial reasons.

An Opportunity to Suffer for the Sins of My Fathers

After college I taught for 3 ½ years in a 65% black/34% Latino middle school in a rough part of Southern California. The school was poor. They had no air conditioning (with temps at 90-100 degrees in September), and no after school sports or music programs. Class size was terrible, averaging 40-42 students per class. Many of the middle school students didn’t come to 7th or 8th grade with their times tables memorized. The “promotion” rate was as high as the “graduation” rate. Fights were extremely common. Many kids were being raised by very young single moms, a grandparent, or foster parents. I began to see upfront what some of the issues are in our society. I-N-E-Q-U-A-L-I-T-Y.

My heart went out to the students. It was the fight of my life to reach them. Many of the students took their frustrations from life out on me. Many of the black students especially hated me as a white teacher. I was called a lot of white slurs in very creative ways. I’m no saint (just ask my bride), but my heart was stirred working at this school as I recalled my childhood elementary school. I wanted to lay down my life for these kids. I wanted to suffer for them. I wanted their frustrations towards their lives and the system they found themselves in to come out. I was willing to bear their pain and their insults. In some way I felt I deserved it. The sins of my fathers (not my own personal ones) needed atoning. I felt it incredibly unfair that I was raised under wonderful conditions, a great school, and a strong community in comparison with what I was witnessing. If they want to hate “the man,” then I felt like they could go ahead and take it out on me. I wanted to show them that this guy may be white, but that he won’t give up, attack back, or stop trying to reach them. I strove to return curses with blessings, and most importantly, to love. Jesus refined me daily in these fires.

All of my favorite experiences at that school involved trying to win over kids that gave me the hardest time or hated me the most. My faith was so fresh! I believed the love of God could wear down anybody. One of my 8th grade black students put up quite a battle towards me for many months. One day I got an idea. Tiger Woods had become all the rage in golf in the 90’s and I had started to play. This young guy (an athlete) who was battling me had an interest in the game since Tiger made it look so cool. But he had never played. I told him to ask permission from his mother to stay after school the next day because I was going to take him golfing. He was stunned! We played 9 holes at a small course near by and this kid’s smile went from ear to ear the whole time. What a thrill it was to watch him! Do I have to tell you that this young lad gave me no trouble the rest of the year? We had a special connection moving forward. Love wins. Oh, how I loved to try to win people over! It didn’t always work, of course, but I laid it all out there.

Years later in Arkansas I taught at an all-black high school for a year. The school was not in an all-black area, however. There was quite a bit of white-flight. Several Little Rock high schools were all or mostly black at that time for the same reason. I encountered improved white slurs at that high school but set out to win over and build connections once again. Loving people is fun. Loving people that hate you is even more fun. Really hard, but fun. I gave the kids the best I had and was able to connect once again with some of the strongest white-guy haters. It is a powerful feeling to break down walls. I can never shake that feeling from my elementary school playground that this racial division thing just shouldn’t be that way… and that it would take a lot of love and a willingness to suffer in order to change things.

A History-Altering Phone Call

Fast forward to 2009. Keri and I decided to embrace a marriage-long dream to adopt. We submitted all of our paperwork (Keri submitted it actually. She’s amazing! There’s a LOT of paperwork.) to become foster-to-adopt parents. We put in for any race child, nearly any situation in terms of health, ages 0-7. After obtaining our license in January, we got a call on Friday, May 29th at 10 am saying they had an African-American baby boy that needed a home. Now this is foster-to-adopt, so you have to foster for months or years before possible adoption becomes available. I was a little shocked they were placing a black baby with us white folk; I was kind of expecting maybe a Latino baby given our really pale skin tones. But, hey, we’re good – bring that lil baby over!

Two hours later they said, “Oops, it’s a girl. An African-American girl.” Keri holds the phone and calls across the room, “Hey, actually the baby is a girl, an African-American girl.” Now, how do you get that wrong, I’m thinking? I reason for like 2 milliseconds, “Well, we were leaning towards wanting a baby boy given having two girls already, but hey, we got the bikes and clothes and such for girls, and this is a baby, so that’s great!” “Honey, bring her over!” That afternoon 3-day-old Nylah was placed on our kitchen counter with some formula and the next chapter began.

Our journey with Nylah has been great. When we are out and about, she gets a million compliments on her beauty from people of all colors. Truthfully, the contrast in our skin colors brings her a lot of positive attention. She has VERY high self-esteem. There are some super painful parts too. Any adoptive kid longs to see themselves in their parents and this is more difficult for her given the wide gap in our appearances. We have just recently become engaged in getting to know many of Nylah’s birth family so we are hoping this piece of the puzzle will be filled in.

God’s Eye-Opening Stages

There are lots of other stories I can share, but I fear I may have reached your listening limit. In summary, my main points are these:

- God used a mostly-white school situation (and “Roots” I think) to convince me as a young boy that something is wrong racially in our world. It produced in me a strong desire to be part of the healing process.

- God used an African-American man to save both my soul and my life from where it was headed. It’s hard to put into words, but you just get a feeling about certain people. When I met Darius, I just had this feeling that something right was happening right there. And, something “really right” did!

- God placed an African-American child in our family to do something special in her life and in ours, and to bring Glory to Himself. How this will all play out, I don’t know. We know pain will be part of the process, but we believe there will also be joy in the morning. We are trying not to be naïve. We realize the hardest parts of being an inter-racial family are still ahead. We believe that God loves to break down walls between peoples even though it will come at a cost.

In the last days the mountain of the Lord’s temple will be established as the highest of the mountains; it will be exalted above the hills, and all nations will stream to it (Isaiah 2:2).

And they sang a new song, saying: “You are worthy to take the scroll and to open its seals, because you were slain, and with your blood you purchased for God persons from every tribe and language and people and nation (Revelation 5:9).”